Cancers can metastasize when cells shed from a primary tumor and enter the blood stream. I developed a diagnostic tool to isolate these circulating tumor cells and measure their concentration. The device is a microfilter with actively controllable pore size, allowing the operator to release captured cells for collection downstream. This project was developed as part of my Master’s degree at UBC. I published a paper on the device that you can read [here](/Lab on a Chip Paper.pdf). I go into more detail on the same device in [my MASc thesis](/Beattie - Thesis.pdf).

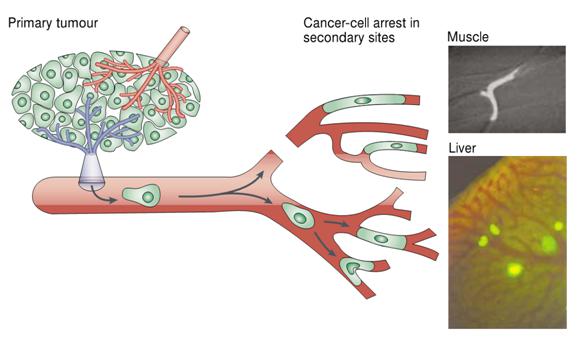

The metastatic process. Circulating tumor cells may be arrested in the microvasculature due to size restriction. Examples of cells arrested in the capillaries of muscle and liver are shown on the right. Image from Chambers et. al., _Nature Reviews Cancer_ 2002

The ability to isolate and count circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in blood would provide a valuable diagnostic marker to oncologists and an important sample source to biologists studying the metastatic process. Despite more than a decade of research and development there exists no satisfactory solution for isolating and enumerating circulating tumor cells in blood.

Our approach uses physical filtration, relying on the supposition that CTCs will be larger and/or more rigid than typical blood cells, a hypothesis supported by the arrest of CTCs observed in the microvasculature.

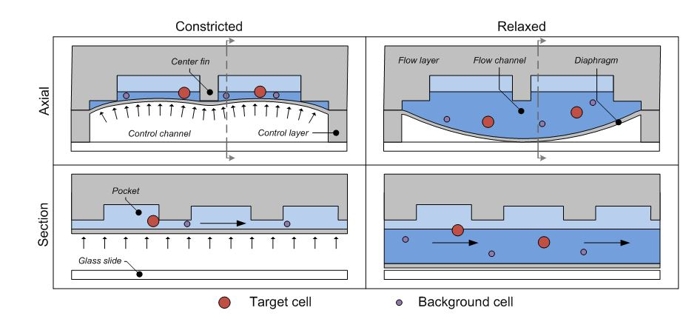

The operating principle of my device. The cell mixture flows through a channel which is dynamically adjusted into one of two states: in the first, the channel is open and all cells pass through. In the second, the channel is semi-closed and only sufficiently small or flexible cells are able to pass

An ideal filtration system should be inexpensive, biocompatible, optically transparent, and should support features on the micron length scale as cells are typically ~10um in diameter. To meet these requirements, we turned to microfluidic technology.

Below is a video of my microfluidic filter in action. The device filters a mixture of white blood cells (fluorescing blue) and cultured bladder cancer cells (fluorescing green). I’ll discuss the process in more detail in future posts.

Microscopy video showing a mixture of cells being separated by the device. I suggest you switch to fullscreen to better see the cells.